Argentina has had staggering inflation rates, multiple stints with debt defaults, and is a massive welfare state. We’re tracing the factors that pushed this once-prosperous nation to the brink. And now, with a presidential candidate advocating for full dollarization, Javier Milei, the future of Argentina’s economy hangs in the balance. Will dollarization be the saving grace or another misstep in a long line of bad economic policies?

History Lesson

Argentina declared independence from Spain in 1816, after which it opened its economy to foreign trade. Argentina sold bonds in London to help finance itself. When the Bank of England raised interest rates in 1825, Argentina became wobbly on the debt it owed and failed to keep up. Two years later, Argentina defaulted on its debt, and it was not for another 30 years that it was able to resume its debt payments.

In the late 1800s, Argentina began borrowing large sums to rapidly build up its infrastructure and transportation services. London’s Barings Bank invested in Argentina’s railroad and utility undertakings, while rural Argentina saw a boom in sheep farming and gold prospecting surpluses. All of a sudden, a speculative bubble on commodities burst, and forced the country to stop its debt payments. This caused a run on Argentina’s banks and resignation of the president, Miguel Juarez Celman. Argentina borrowed more money from the U.K. to prevent total insolvency.

A rise in immigration and foreign capital into Argentina led it to rise to be one of richest countries in the world by the early 1900s. In 1913, Argentina was one of the top 10 wealthiest countries in the world with strong economic growth and a smooth-running modernization plan. But, the First World War and the Great Depression wrecked these gains, causing unemployment and social unrest.

Then, in 1930, a military coup replaced the 1853 constitution with a fascist-style corporatist government that was hostile toward private commerce. A period of political instability ensued, with eight different presidents in two decades. A policy of import substitution reigned, sealing the economy off from the rest of the world and leading to another default.

General Juan Peron rose to power in 1946, nationalizing companies, redistributing wealth, and asserting state control over the economy. He was an admirer of Benito Mussolini and the Italian Fascist regime, and applied some of the corporatist principles in his overturning of the country’s free market economy.

Learn the benefits of becoming a Valuetainment Member and subscribe today!

In 1955, Peron was ousted in a coup, breaking the economy and eliminating Argentina’s chances for paying its debts yet again. Even though he was removed, the political culture that Peron and his wife Evia (whom Madonna played in a 1996 film) sewed would become embedded into the country’s identity for the next seven decades.

1956, the military junta struck a deal with the “Paris Club,” a group of creditor nations, to prevent a greater default. Argentina borrowed money primarily from U.S. and U.K. banks to fund infrastructure projects and state-owned industries during the “Dirty War” of 1974 to 1983, a period of state-backed terror against communist insurgents. The nation’s foreign debt skyrocketed from $8 billion to $46 billion.

Commodity prices collapsed when the Federal Reserve under Chairman Paul Volcker raised U.S. interest rates as high as 20% to handle inflation. This caused a debt crisis not only in Argentina but throughout South America and the rest of the developing world. Argentina was one of 27 nations, including 16 in Latin America, to restructure its debt. With higher rates comes a stronger dollar, and with a stronger dollar debt payments get more expensive for foreign countries.

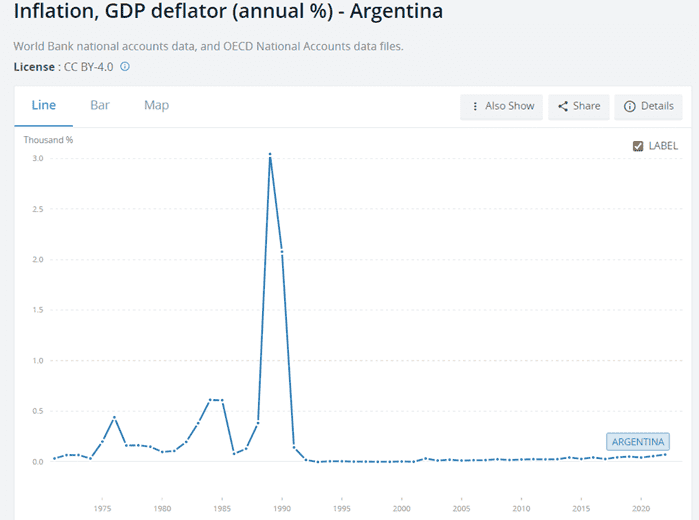

To contain the recession that followed from the crisis, Argentina started printing money. Inflation rose to over 3,000%, forcing another default in 1989. This brought Peronist leader Carlos Menem into power, who brought down inflation, privatized formerly state-owned companies, and attracted foreign direct investment. This sent Argentina from recession to “double-digit growth” by Menem’s second year.

But Menem was unable to stop spending. The country’s foreign debts rose to more than $100 billion. By the time he exited office in 1999, Argentina had fallen into recession again with rising unemployment, constrained exports, and overvalued currency.

Four years of economic desolation led to the loss of roughly two-thirds of Argentina’s GDP. Argentines called for change, uniting around the rallying cry, “All of them must go!” They had five different presidents in the span of two weeks and declared a default, in what was at the time the largest default of any country in history.

Argentina ceased payments on $95 billion of bonds, leading to a restructuring where President Nestor Kirchner and his wife Cristina Fernandez renegotiated deals with creditors between 2005 and 2010. Most bondholders in the deal intended to show mercy, agreeing to take 30 cents on the dollar offered, but American billionaire financier Paul Singer successfully held out and pushed for full repayment. A legal drama commenced, leading Argentina to default.

A new president, Mauricio Marci, won on a platform of fiscal austerity and pro-market reforms in 2016. Marci paid the holdout creditors led by Singer so Argentina could re-gain access to international debt markets, and subsequently took billions in financing from foreign creditors.

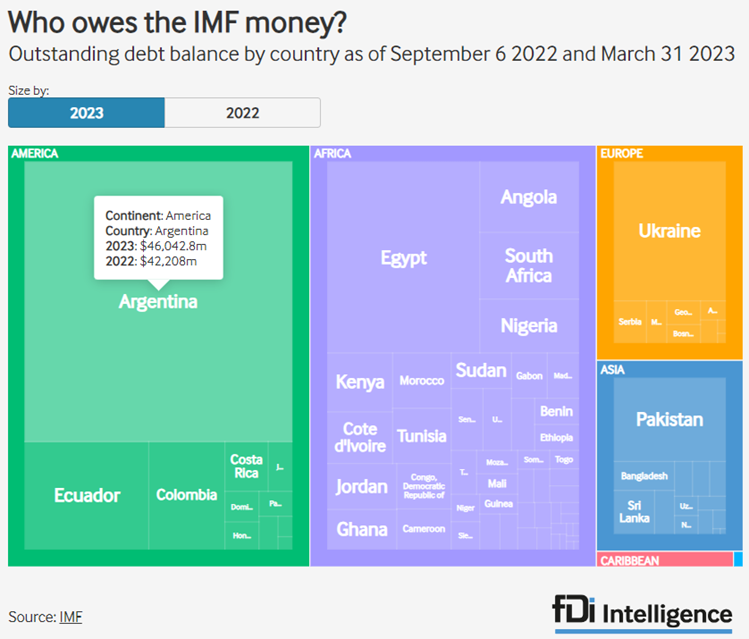

However, Marci reform agenda hit a roadblock in congress. The economy continued to lag, and the country remained saddled with a debt burden. The country’s leaders scrambled to the IMF in 2018 and successfully begged for a $56 billion credit line, the largest aid package the IMF ever gave.

But it did not make a difference. Investors pulled money out of Argentina at a rapid pace because they assumed nothing would change and collapses would continue to happen. The death knell struck when leftist leader from the Kirchner administration Alberto Fernandez won in a primary vote landslide in August 2019, virtually guaranteeing a victory over Macri. The very next day, investors flocked away, plummeting Argentine bond prices to less than 50 cents on the dollar.

Inflation

The so-called “Peronists,” which are effectively still ruling Argentina as of today under President Alberto Fernandez, plunder the nation’s citizenry to fight off its perpetual bankruptcy problems and cause crippling inflation. Today, 4 out of 10 Argentinians are living in poverty.

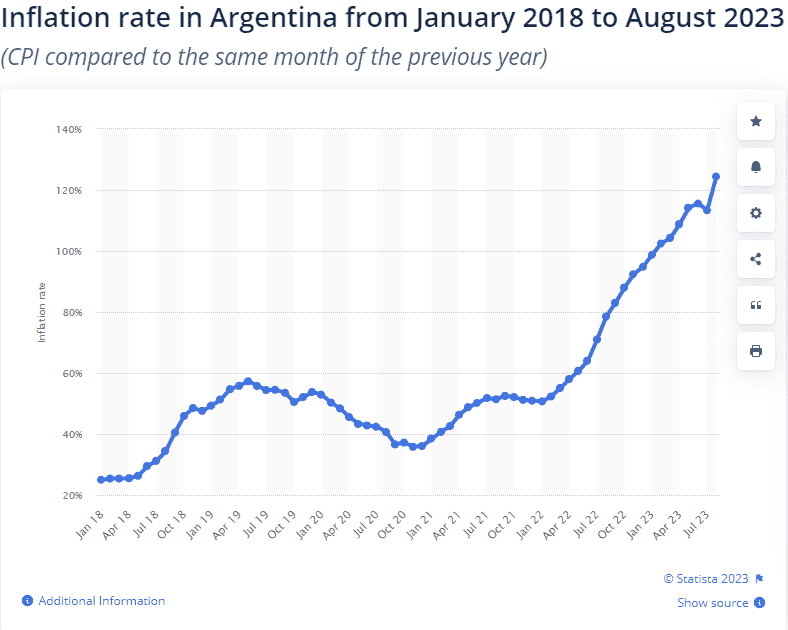

In January 2018, Argentina’s inflation rate hovered around 25%. By January 2023, it had jumped up to 100%. Now, as of August 2023, its inflation is at 124.4% compared to what it was at this same time last year.

But this is not even the worst inflation Argentina has experienced. In 1989, Argentina had an inflation rate of 3,000%.

Welfare Mindset

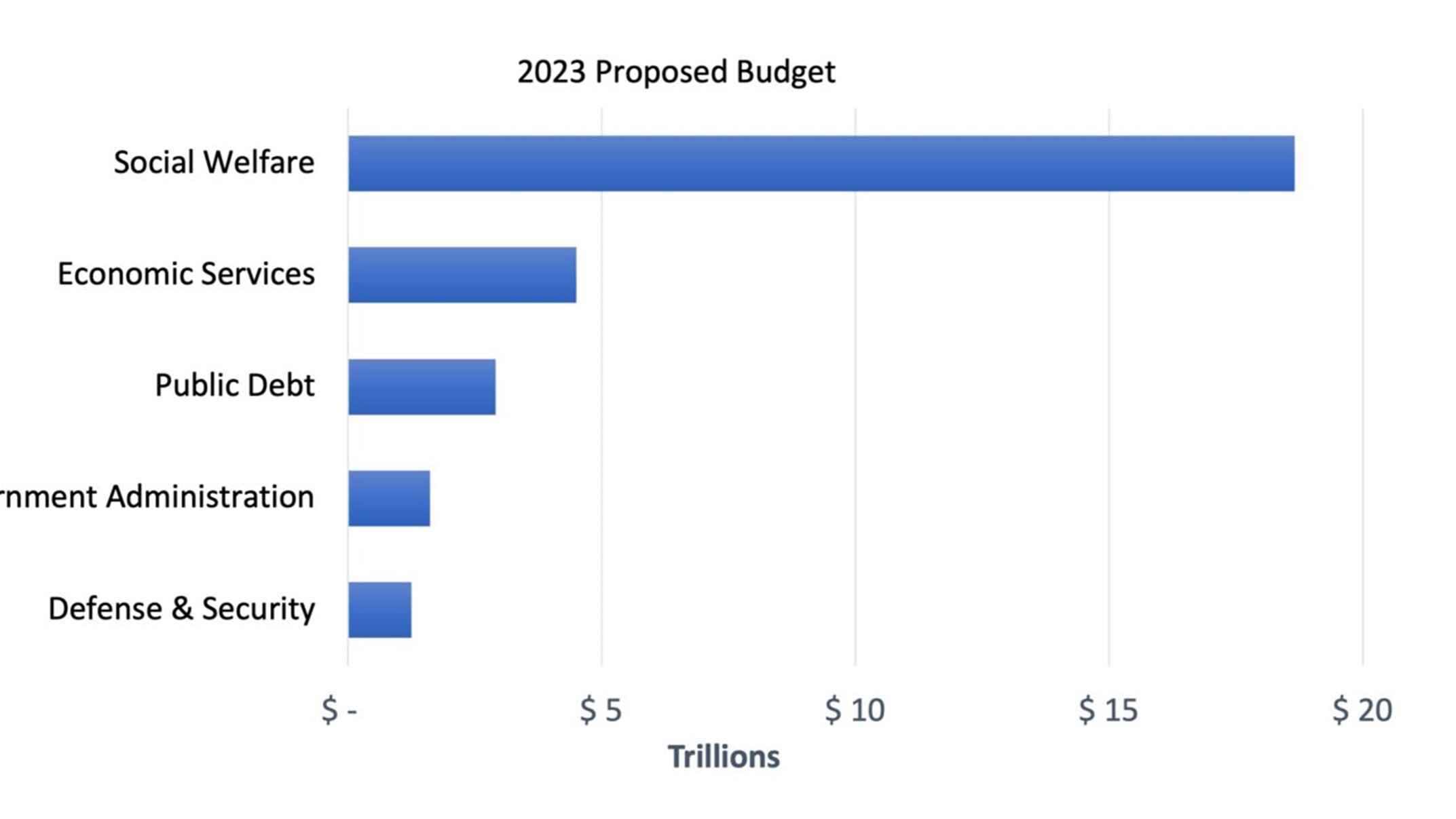

How is this happening? What is Argentina spending its money on? According to their 2023 national budget, that answer would appear to be welfare. In 2023, Argentina’s lower house approved a national budget that would spend 29 trillion pesos ($183 billion U.S. dollars), of which roughly $18 trillion, or 62%, was directed to be spent on social welfare. Another $4 trillion was to be spent on “Economic Services,” which does not include public debt spending or government administration.

It would seem that Argentina is still not learning any lessons from the 9 times it has defaulted on its debt, as it is now looking down the barrel of yet another.

A good example of Argentinian domestic spending is agriculture subsidies. Argentina leads the world in subsidizing its agriculture industry, a practice that one does not exactly want to lead in. Corporate welfare, otherwise known as “crony capitalism,” actively hurts the market as it does not allow prices to actually signal demand, and so companies are less able to respond to need. This allows them to collect profits in virtual monopolies on the backs of the workers, all while getting passed off as noble. Argentina is paying out of its national GDP for its agricultural produce.

To combat rampant inflation, Argentina puts price caps on some 1,400 commodities. More than a third of its workforce is employed by the government. Instead of investing into innovation, technology, and so on, Argentina has to put all of its money into basic things like keeping prices of food down.

Argentina is the biggest borrower of the IMF and represents 1/3 of all IMF debt.

In August 2023, Argentina’s economic minister Sergio Massa said Argentina would not use “a single dollar of its own reserves” to make the IMF repayment. It has engaged in other measures to prevent dollars from leaving its country, such as capping what exports Argentines can make.

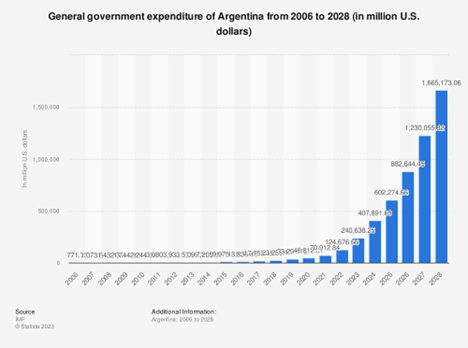

And according to statistical projections, Argentina’s government expenditures are only going to rise from here.

Javier Milei

The leading presidential candidate for Argentina is Javier Milei, a strange, fiery self-described anarcho-capitalist. Milei wants Argentina to engage in dollarization, in which the country would give up its ability to print its own money so that inflation can be stopped from above.

But it is very hard to kick an addictive habit, and it is not certain someone like Milei can win. Welfare dependents do not want to give up on their entitlements, and saving the Argentinian economy will doubtlessly require a curbing of welfare spending. This should serve as a warning to America and other western countries that are engaging in ever-higher levels of government spending.

Add comment